Damn Cute Menace

One man's war and uneasy peace with the squirrels of Los Angeles

By David Page (Los Angeles Times Magazine, June 3, 2007)

Best Magazine Feature, 2007 (Outdoor Writers Association of California)

Best Magazine Feature, 2007 (Outdoor Writers Association of California)

A squirrel leaping from bough to bough, and making the wood but one wide tree for his pleasure, fills the eye not less than a lion,—is beautiful, self-sufficing, and stands then and there for nature.

— RALPH WALDO EMERSON

hey come in off the utility lines. Like airborne chipper- shredders they dispense with the season's pecans, tear yards of bark from the avocado tree, send half-chewed fruit, seeds, shells, leaves, whole limbs crashing to the flagstone. Screeching like harpies, they hang by their claws within inches of our dog's nose, taunting him beyond reason. They've chewed through our phone line, severed our connection to the Internet. They've killed our apricot tree.

hey come in off the utility lines. Like airborne chipper- shredders they dispense with the season's pecans, tear yards of bark from the avocado tree, send half-chewed fruit, seeds, shells, leaves, whole limbs crashing to the flagstone. Screeching like harpies, they hang by their claws within inches of our dog's nose, taunting him beyond reason. They've chewed through our phone line, severed our connection to the Internet. They've killed our apricot tree.

And still my wife thinks I should put away the gun.

When Thoreau wrote that "in Wildness is the preservation of the world," squirrels may have been foremost on his mind, their play beneath the floorboards distracting him from his work. "[W]hen I stamped they only chirruped the louder," he wrote, "as if past all fear and respect in their mad pranks, defying humanity to stop them."

When I poison rats in our attic, my wife is relieved. For field mice in the kitchen, she prefers I bait them with peanut butter and snap their little necks. But squirrels—squirrels are a different matter.

When the city of Santa Monica tried to poison a colony of ground squirrels in a local park in 2005, then again in early 2006, the result was public outcry—and an increase in the number of squirrels. The city turned to Frazier Park "rodenator" Lefty Ayers, who, according to a recent story in The Times, live-trapped 165 of the disease-ridden nibblers and "euthanized them with carbon dioxide." The carcasses were fed to rehabilitated hawks. Still, animal-rights activists "hounded Ayers, destroyed his traps and tried to steal supplies out of his truck." Now the city plans to implement a costly program of squirrel birth-control injections.

"I understand squirrels are cute," Ayers told The Times, "but if they were rats or cockroaches, would they get the same treatment?"

"I understand squirrels are cute," Ayers told The Times, "but if they were rats or cockroaches, would they get the same treatment?"

Long celebrated in painting, poetry and literature, they now appear regularly on television and in the movies. The Web is overrun with fan sites: squirrels.org, thesquirrelloversclub.com, squirrels-r-forever.com. There are virtual treehouses for squirrels, online emporia hawking feeders, fine-art prints, books and rehab supplies. Squirrel-rehab.org has been "helping orphaned squirrels since 1991."

One Orange County-based enthusiast provides an online ranking of colleges and universities according to the premise that "[t]he quality of an institution of higher learning can often be determined by the size, health and behavior of the squirrel population on campus." (He gives UCLA a "three-squirrel" rating. UC Irvine only one. Cal State Fullerton, for having allegedly poisoned its colony of ground squirrels, earns a shameful "one squirrel minus." Competition is fierce between Cal and Stanford for the best "critter quality" nationwide. Berkeley wins, with five squirrels to Stanford's four-plus.)

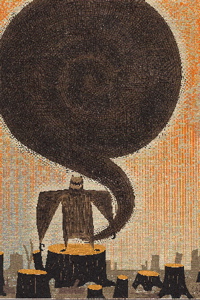

Once they were the tenders of a healthy forest; they kept the canopy pruned, aerated the soil and planted seeds. In some parts of the world they still perform these functions. Here in Silver Lake, once they've finished with the trees, they will eat roofing shingles. And radiator hoses. According to the current L.A. County agricultural commissioner, "[t]ree squirrels damage green and ripe walnuts, almonds, oranges, avocados, apples, strawberries, tomatoes and grains. Telephone and electrical lines are sometimes gnawed, and they also chew on buildings or invade attics through knotholes."

Last year a woman in suburban Chicago was "scratched in the leg and bitten by a squirrel as she walked from her porch to her car." A squirrel tore into several people at a park in Florida, including two 3-year-olds; another jumped a postal employee in Oil City, Pa. A Minnesota woman died of propane inhalation "after a squirrel became lodged in a pipe between the furnace and the chimney." Squirrels may carry "rabies, toxoplasmosis, bubonic plague, western encephalitis, encephalomyocarditis, murine typhus, tularemia, endemic relapsing fever and ringworm, all of which are transmissible to humans." And West Nile virus.

It was when they ate the last handful of blossoms on our 80-year- old apricot tree that I bought the rifle: a vintage Crosman Pumpmaster 760, a BB gun that doubles as a pellet shooter. It cost me $20. Aside from its Lone Ranger styling and modern materials, it is similar to the air rifle Meriwether Lewis used to bag squirrels—and to "astonish the nativs [sic]" (as Capt. Clark put it in his journal in 1804). It may look like a toy. But as generations of fathers have admonished generations of sons, it is not; it's a weapon. Children in Indiana and Alabama have used the Crosman 760 to accidentally shoot friends and neighbors dead.

The squirrels in my trees are eastern fox squirrels. Sometimes mistakenly referred to as red squirrels, or red fox squirrels—even by the California Department of Fish and Game—they are as native to California as the trees themselves. Which is to say they are not native at all. They first appeared in Los Angeles around 1904, having made their way from the Mississippi Valley, across rivers and mountains, most likely on Collis P. Huntington's Southern Pacific Railroad, stowed in the baggage of Civil and Spanish-American War veterans. Maybe they made good pets. Maybe they made for better stew than local squirrels.

Cities will import wildness "at any price," wrote Thoreau. So it was that in 1912, Huntington's nephew, Henry, ordered a pair of fox squirrels from New York to enhance his gardens in San Marino. So it was that factory workers from Iowa were said to have imported them to Long Beach during World War II to help ease their homesickness. So it was that, against all advice, a board member of a country club in Bakersfield thought it a fine idea in 1985 to bring two dozen from Fresno.

"When the [fox] squirrels first appeared," wrote onetime L. A. County Deputy Agricultural Commissioner Elmer Becker, "even the walnut growers thought they were 'cute.'" By 1933 it was declared "unlawful to import, transport, possess or release alive into this state" a whole range of "wild" animals, including all but a few domesticated species of the order rodentia. It was too late. In 1947, Becker wrote that "about half the phones reported out of service after a rainstorm mean squirrel damage."

Many who wanted to rid themselves of the pests contributed instead to their proliferation. In 2004, Julie King, then a graduate student at Cal State Los Angeles, and her advisor, Dr. Alan Muchlinski, conducted an online survey to track distribution patterns. One citizen admitted: "I have trapped five fox squirrels that were destructive to my garden and released them at golf courses." Another confessed to having captured 23, then "moved them to a park near USC."

Not only have we transported them from place to place, we've also insulated them from the pressures of natural selection. We've stopped eating them, stopped using their pelts to make robes and slippers. We've planted for them a veritable Eden of fruit and nut trees, and constructed, as if expressly to protect them from predators (and cars), a vast network of overhead utility lines. (Southern California Edison alone boasts more than 70,000 circuit miles--surely the largest artificial wildlife corridor ever conceived.) And still, wildlife rehab organizations rescue hundreds of injured or orphaned fox squirrels every year and release them "in the wild."

"As we keep moving out," says Muchlinski, "the fox squirrel is going to go right along with us." From Montreal to Mexico City, from Seattle to Raleigh-Durham, in Florida and in Manhattan's Central Park, the various subspecies of fox squirrel chew on their surroundings. Local species, meanwhile, have proved "more sensitive to habitat fragmentation." Faced with the relentless creep of plywood castles, California's western gray, the one John Muir called "the handsomest of all," cousin to the Oregon native first described (then most likely eaten) by Meriwether Lewis, is under pressure.

"There's not much you can do," says Muchlinski, describing a routine explosion of apricot fodder in his yard in West Covina. "I enjoy seeing them," he adds, "as much as having an apricot tree and getting some apricots."

*

A squirrel is just a rat with a cuter outfit.

— SARAH JESSICA PARKER in "Sex and the City"

ome and garden catalogs offer an arsenal of "harmless" solutions, from the Squirrel Evictor MB10K strobe-light, to the Rotating-Head Owl, to Old Doc's Squirrel Chasers. Harmless indeed. According to the University of California's Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, "[t]ree squirrels quickly become habituated to visual or sound frightening devices and pay little attention to them after a couple of days."

ome and garden catalogs offer an arsenal of "harmless" solutions, from the Squirrel Evictor MB10K strobe-light, to the Rotating-Head Owl, to Old Doc's Squirrel Chasers. Harmless indeed. According to the University of California's Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, "[t]ree squirrels quickly become habituated to visual or sound frightening devices and pay little attention to them after a couple of days."

"I don't know any way to control them," says Los Angeles tree specialist Steve Marshall, "except to kill them—and they are numberless."

Traps may be used according to certain specifications, as long as live animals are not transported or released other than where they were caught. Trees can be trimmed, but according to the UC's pest management program, "it is virtually impossible to keep squirrels out . . . because of their superb climbing and jumping ability." My neighbor cut down all his trees, and still the squirrels venture onto his porch to get his birdseed.

Fox squirrels are classified as game mammals under the Fish and Game Code. Which means that in certain counties anyone with a weapon and a hunting license, in season, can legally kill and have in his or her possession four "red fox squirrels" per day. For those who prefer bows and arrows, or falcons, the season opens earlier.

There is no official hunting season in L.A. County. However, "red fox squirrels that are found to be injuring growing crops or other property may be taken at any time or in any manner," including in Los Angeles. The municipal code does prohibit the discharge of firearms (or the projecting of arrows or missiles of any kind) within range of houses, streets or parks, but the state code—in a handy variation to the 2nd Amendment—

may provide a loophole: "when necessary so to do to protect life or property, or to destroy or kill any predatory or dangerous animal."

An old-timer in Glendale grows award-winning tomatoes—and has a keen interest in firearms. To keep squirrels from his seedlings, he uses a Chinese Model 62 that delivers a lead pellet with 1,000 pounds of pressure.

*

I made my dog take as many each day as I had occation for, they wer fat and I thought them when fryed a Pleasent food.

— MERIWETHER LEWIS

he idea, at least at first, was not to kill them, but just to give a little bite to the dog's bark. I've sent any number scrambling for an exit. I've shot several clean off branches. Most managed to skitter to safety before the dog could react. Before I could reload. Others—three, I think it was—never got up.

he idea, at least at first, was not to kill them, but just to give a little bite to the dog's bark. I've sent any number scrambling for an exit. I've shot several clean off branches. Most managed to skitter to safety before the dog could react. Before I could reload. Others—three, I think it was—never got up.

The first dropped onto my neighbor's patio. With my avocado picker I fished him over the fence, stuffed him into the yard-waste bin, swore to myself that enough was enough, that I had no right, and so forth. My son is not yet 2 years old. What am I teaching him? Watch as Daddy inserts pellet into breach, pumps, brings stock to shoulder, takes aim, fires.

A couple of Guatemalans, working next door, witnessed my second kill. They were gleeful. Back in our village, they explained, we eat squirrels.

Want this one? I asked.

No, esta bien. They'd brought their own lunch.

"The way to reestablish ecological balance," writes British philosopher and gentleman-farmer Roger Scruton in his book "News From Somewhere," "is to acquire the habit of eating your competitors." Of his local grays, he writes: "You need four per person—not because they are particularly small, but because they are surpassingly delicious."

Of the third kill, I can't recall a single detail.

My little rifle and I have had no effect on the mushrooming population of exotic rodents in the American West. Two months after the phone cable was repaired, there was again static on the line. Even as I write this I can hear them chattering away, avocado fragments hailing upon the deck, each a tangible representation of fruit that will not make this fall's guacamole.

I tell myself I should not think of the trees as property.

I tell myself I should study falconry or ferreting. Or get a rodent-eating snake.

Or I could abandon all pretense to lucrative employment, install myself in a deck chair to guard my patch of urban forest like Baby Doe Tabor atop her played-out Colorado gold mine. I could upgrade my ammo, raise my son on squirrel stew, avocado and pecan pie.

Another alternative would be to sell our house and move out beyond the squirrels—to Antarctica, say—and participate in some other problem.

Or I could list the gun on eBay, per my wife’s wishes, and let the yard, and the earth with it, go the way it will.

Post a Comment

Post a Comment